-johnqdewars.blogspot.com

by CR Abrar

At a press conference on August 11 and at another consultation the next day, the information minister attempted to assuage growing public concern about the broadcasting policy that his ministry had framed. He insisted that it had been formulated to help the electronic media flourish on its own and reduce government control over it. Stating it a guideline and denying it being ‘authoritarian’, he dismissed the suggestion that ‘the policy intends to strangle the media… (as)… baseless and imaginary.’ He went on to claim ‘its every provision is beneficial and helpful for the media.’ He also expressed his commitment to upholding ‘editorial sovereignty’ and trashed the allegation that the policy did not reflect the opinions of the stakeholders and members of the committee that drafted the policy. It is only those who did not understand it are criticising the policy and misrepresenting it, he argued.

Since the passage of the policy, the media have reported widespread reaction that it elicited. Except for a handful of individuals and associations, the overwhelming segment of those responses was apprehensive of the motive of the government. Included among them were several members of the committee representing the journalist community as well as the broadcasting establishment. Their somewhat muted criticisms conveyed volumes about their disappointment with the new policy. In the meantime, the advertisement industry, again led by people perceived to be favourably disposed to the government, has also voiced its concerns about the policy. The president of the Bangladesh Advertising Agency Association, Ramendu Majumdar, is on record lamenting that most of the association’s suggestions have been left out in the policy. Understandably, the policy also drew sharp criticism of rights activists, public intellectuals as well opposition political parties. Many categorically rejected of what they termed ‘freedom curbing’ policy.

The ministerial clarification has done very little to mitigate the concerns expressed by various quarters. In fact, his outright rejection of the call for immediately setting up an independent commission, at least before drawing up the legislation, has sent out a clear signal that the administration cares little about public anxiety. It also reflected the mental frame of the ruling elite that its prerogative to decide what is in the pubic interest is definitive and cannot be questioned by anyone else, not even by key stakeholders.

There is little doubt that in conditions of shrinking democratic space and general intolerance of contra views such a policy would have major bearing on the broadcasting law now being mulled. The measures proposed in the policy details out the control mechanism that would be put in place once the new law is framed around it. Clearly, some of the provisions are blatantly directed to thwart the broadcasting of footage indicating the government’s failure, irregularities and repression.

The government is disappointed at the performance of private channels, some of which are broadcasting programmes that have not been in tune with what it likes. In a situation where pervasive use of force and litigation has virtually emasculated the political opposition, the bold reporting of the media on the excesses of the executive arm of the state, rampant corruption and arbitrary use of force by the members of the law enforcement agencies, among other things, made it a very important for the people keen to secure balanced information. The television footages on the infamous seven murders in Narayanganj and the accompanying investigative reporting by the media forced the administration to bring a section of the powerful perpetrators to task.

Weighed down by misinformation propagated by the state-run channels and a section of private channels, another section began drawing interest of the politically conscious citizenry of the country. The discussion sessions, the so-called talk-shows, hosted by these channels provide a refreshing setting, particularly for those who are hungry for reflection and analysis of events as and whey they occur. They find such programmes rewarding as they help them getting closer to the truth and in shaping their own opinion through their exposure to contending perspectives. Not everyone is in sync though, a powerful few find the talk-shows ‘tak’ (sour) and have candidly shared such feelings.

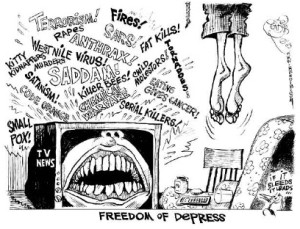

The administration, therefore, has opted to bring in line those channels that respond to the market forces, ie, popular demands for unbiased reporting and differing perspectives. Hence, its insistence on streamlining the contents of the news and talk-shows. The inclusion of the provision to include government programmes mandatory for private channels will invariably result in those channels meeting the same fate as that of Bangladesh Television and Radio, losing credibility and audience and their trust. So instead of helping the electronic media to prosper, the administration is on course to incapacitate them. Its final goal is to ensure pervasive conformism.

Quite a few provisions of the policy appear to be superfluous. The extra emphasis on national security, the forewarning about reporting on issues that impinges on national security and sovereignty, spirit of the war of national liberation, national culture and tradition and law enforcement agencies are quite unnecessary and uncalled for. There has hardly been any example where the media have faltered in reporting on these issues. The administration’s extra-sensitivity about reporting on friendly countries only validates the prevailing public perception about its overt dependence on our powerful neighbour. Perhaps such a provision in the national broadcasting policy is a way of paying back the piper for the support it extended at a critical time at the beginning of the year and continuing to do so.

One does not have to be a sage to realise that media control can lead to catastrophic consequence for the political leadership. The absence of alternative sources of information would invariably lead to their increased dependence on administrative or party sources or those of intelligence agencies. In most instances, cronies and sycophants staff these channels who instead of furnishing fair and balanced information, do so in the form and manner that political leadership wants them to provide. Successive authoritarian administrations in this country learnt the hazards that lay in taking such a path. It leads to a plethora of freedom-curbing anti-democratic policies and further alienation of the rulers from the ruled. One wonders if the current administration is wittingly treading that path or not.

CR Abrar teaches international relations at the University of Dhaka. He is president of Odhikar.